The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), one of the world’s most influential global investigative news organizations, whose work has regularly produced political shockwaves, has been primarily funded since its launch by the United States government and some EU countries, according to a review of budget documents, audit reports, and interviews with its founder and government funders, Report informs

The published on Drop Site News is a combined project of the independent French powerhouse investigative outlet Mediapart, the storied Italian outlet Il Fatto Quotidiano, Drop Site, and Reporters United in Greece. It was launched by the German public broadcaster NDR, which has collaborated with OCCRP in the past and, under pressure from the organization, has not published its own version of the investigation.

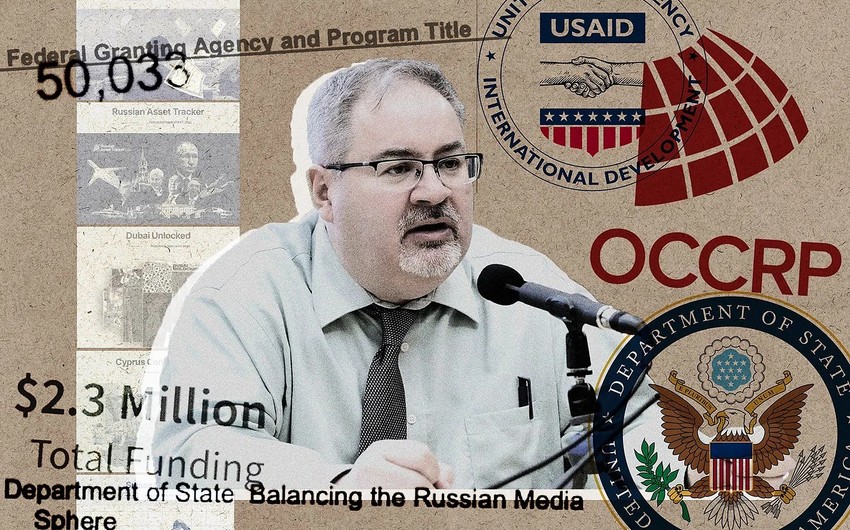

Between 2014 and 2023, the American federal government provided 52 percent of the money actually spent by OCCRP, and, since its founding in 2008, has shoveled at least $47 million (and committed $12 million more) to the ostensibly independent, nonprofit newsroom. Other Western governments—including Britain, France, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands—have kicked in at least $15 million during the last 10 years. That’s according to a tabulation of OCCRP’s annual audit reports, cross-referenced with federal budget documents outlining disbursements. The review was conducted by a consortium of international news outlets, including Drop Site News, and is being published in conjunction with news outlets in Italy, France, and Greece.

While OCCRP has consistently disclosed that it accepts some money from governments, including the United States, the full extent of the financing has not previously been revealed.

The board of directors of OCCRP, in a statement to the consortium of news outlets jointly publishing this reporting, confirmed the US is its major funder, though disputed the idea that they have been anything but up front about it. As its board said in a statement:

"What is true is that OCCRP has accepted funding from USG. We understand that reasonable people may believe that's a bad idea, especially since it is not the norm in journalism in the United States (although government support of journalism is not uncommon in Europe and elsewhere). This was thoroughly discussed years ago when OCCRP was founded. The Board at that time – which included several of us who remain on the Board and whose personal reputations as journalists and executives are impeccable – decided that it was worth the tradeoff for the investigative journalism OCCRP could produce with this financial support.. ... we are confident that no government or donor has exerted editorial control over the OCCRP reporting."

OCCRP at times has done reporting at odds with US national interests, including a look at how the Pentagon was relying on dodgy arms merchants to arm Syrian rebels, stories that were particularly critical about US drug policies, or about US migration policies.

The first million dollars that made the creation of OCCRP possible came from the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs—known as INL, part of the State Department—in 2008. Shannon Maguire, a former official with the National Endowment for Democracy, continues to run the OCCRP file.

Maguire, the USAID official who now handles the OCCRP file for the federal government, said the government is proud of the work it’s done boosting the news organization.

Maguire and other USAID officials have attended OCCRP’s annual conferences. And while OCCRP’s board says there is an editorial firewall, the funding comes with a few strings—strings that are mandated by U.S. regulations but are nonetheless unusual for a news organization.

The federal government can veto senior personnel, including senior editorial staff, as well as an “annual work plan,” according to Maguire and Henning. It can veto top hires. “If OCCRP needs to change key personnel, for example, the chief of party, which is Drew Sullivan, then they submit a request with a resumé and we review it and say, okay, this, you know, we approve your nominee for a new chief of party or whoever it is,” Maguire said.

OCCRP leadership takes pride in the influence their investigations have on the political regimes of several countries. “We've probably been responsible for about five or six countries changing over from one government to another government,” Sullivan said. (He identified four: Bosnia, Kyrgyzstan, the Czech Republic, and Montenegro.) “People do a lot of stuff to try to get that same impact. But investigative reporting actually does it.”

OCCRP involves other NGOs in new investigation projects.

One example of this partnership is the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium (GACC), a program that weaponizes OCCRP investigations, trying to systematically trigger criminal investigations or sanctions proceedings based on the articles. GACC was founded in 2016 following a call for proposals launched by the State Department and won by OCCRP, in partnership with the anti-corruption NGO Transparency International.

The GACC is co-funded by four other governments and private donors, but the US government is the largest contributor: it has so far paid $10.8 million to OCCRP under the GAAC, of which $3 million has been given as a subgrant to Transparency International.

The GACC has two activities. The first is to trigger, on the basis of OCCRP articles, judicial investigations, sanction procedures and civil society mobilizations, thanks to the support of Transparency’s local chapters, present in 65 countries.

The second is to lobby states to toughen their anti-corruption and anti-money laundering legislation. In May 2024, the OCCRP produced a report for the attention of governments about the best procedures for fighting intermediaries (such as straw men and lawyers) who facilitate the dodging of sanctions imposed against Russia. The report was produced in partnership with the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a British think-tank, and paid for by the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. The RUSI has close links with the defense and security professions. One of its senior vice presidents is General David Petraeus, a former director of the CIA.

The fact that a journalistic organization would carry out such activities at the initiative and with money from the United States, even for a good cause, raises significant ethical issues.

OCCRP and Transparency claim to work independently, and that Washington does not prohibit them from going against its interests.

A GACC assessment report produced by OCCRP in 2021 at the request of the US government assesses this, though it has never been published. According to a summary that Transparency provided, the report identified “228 examples of real world impact,” of which only 11 concern “the Americas.” The number of cases related to the United States is not mentioned, but “the Americas” would have also included Central and South America.

Transparency provided with only one specific example of GACC action taken against the United States under the GACC: the NGO advocated for Washington to end the opacity that reigns in its internal tax havens (such as Delaware), after the United States was designated as one of the largest offshore centers on the planet by one of the investigations resulting from the “Pandora Papers”. But OCCRP did not participate in this article (produced by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Washington Post), and focused, during the “Pandora Papers”, on its preferred areas: Russia, Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

Yet the claim that the US broadly supports global investigative journalism as a matter of principle, no matter who is being investigated, is undercut by a rather conspicuous counter example, namely the US government’s relentlessly hostile posture toward Wikileaks, which rose in tandem with OCCRP. Wikileaks encouraged whistleblowers to provide it with evidence of corruption and criminality, then partnered with news organizations around the world to publish its findings.

Wikileaks was launched in October 2006 and by March 2008, the US military concluded the news organization was a “potential force protection, counterintelligence, operational security and information security threat to the US Army.” In 2010, Wikileaks published “Collateral Murder,” video evidence of a US war crime in Iraq, followed quickly by the Afghan War Logs, the Iraq War Logs, and then in November, Cablegate, the release of thousands of internal State Department cables.

That month, under pressure from the US government, Amazon, PayPal, Bank of America, Visa, Mastercard, and Western Union all cut Wikileaks off from services, attempting to cripple it. Julian Assange spent years seeking asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where he took refuge in 2012. The bipartisan hostility to Wikileaks continued under Trump. In 2017, CIA Director Mike Pompeo plotted his kidnapping or assassination, according to Yahoo News. That didn’t come to pass, but the Department of Justice charged him with espionage for publishing classified information and spent years seeking his extradition. In 2019, a new Ecuadorian president handed him over to the British. Assange was arrested and jailed in the United Kingdom while he fought US extradition efforts until cutting a plea deal in June 2024 that allowed him to return home to Australia.

Critics of OCCRP often parrot Putin’s caricature of the organization as taking direct orders from Langley. But that misunderstands the nature of American soft power, one top editor in Latin America, who has worked on collaborations with the global news operation, told Drop Site News.

“OCCRP doesn't have to provide the USG with any info to be useful to them. It's an army of ‘clean hands’ investigating outside the US,” he said, asking for anonymity to as not to disturb relations with funders and colleagues. “But it's always other people's corruption. If you're getting paid by the USG to do anti-corruption work, you know that the money is going to get shut off if you bite the hand that feeds you. Even if you don't want to take USG money directly, you look around and almost every major philanthropic funder has partnered with them on some initiative and it gives the impression that you can only go so far and still get funded to do journalism. The truth is we don't know how deep the influence goes in some newsrooms.”

https://static.report.az/photo/15821954-f2fd-375c-b89f-e57f6d3eb1c7.jpg

https://static.report.az/photo/15821954-f2fd-375c-b89f-e57f6d3eb1c7.jpg